Chapter 12. Managing change with Mercurial Queues

Table of Contents

- The patch management problem

- The prehistory of Mercurial Queues

- The huge advantage of MQ

- Understanding patches

- Getting started with Mercurial Queues

- More about patches

- More on patch management

- Getting the best performance out of MQ

- Updating your patches when the underlying code changes

- Identifying patches

- Useful things to know about

- Managing patches in a repository

- Third party tools for working with patches

- Good ways to work with patches

- MQ cookbook

- Differences between quilt and MQ

The patch management problem

Here is a common scenario: you need to install a software package from source, but you find a bug that you must fix in the source before you can start using the package. You make your changes, forget about the package for a while, and a few months later you need to upgrade to a newer version of the package. If the newer version of the package still has the bug, you must extract your fix from the older source tree and apply it against the newer version. This is a tedious task, and it's easy to make mistakes.

This is a simple case of the “patch management” problem. You have an “upstream” source tree that you can't change; you need to make some local changes on top of the upstream tree; and you'd like to be able to keep those changes separate, so that you can apply them to newer versions of the upstream source.

The patch management problem arises in many situations. Probably the most visible is that a user of an open source software project will contribute a bug fix or new feature to the project's maintainers in the form of a patch.

Distributors of operating systems that include open source software often need to make changes to the packages they distribute so that they will build properly in their environments.

When you have few changes to maintain, it is easy to manage a single patch using the standard diff and patch programs (see the section called “Understanding patches” for a discussion of these tools). Once the number of changes grows, it starts to make sense to maintain patches as discrete “chunks of work,” so that for example a single patch will contain only one bug fix (the patch might modify several files, but it's doing “only one thing”), and you may have a number of such patches for different bugs you need fixed and local changes you require. In this situation, if you submit a bug fix patch to the upstream maintainers of a package and they include your fix in a subsequent release, you can simply drop that single patch when you're updating to the newer release.

Maintaining a single patch against an upstream tree is a little tedious and error-prone, but not difficult. However, the complexity of the problem grows rapidly as the number of patches you have to maintain increases. With more than a tiny number of patches in hand, understanding which ones you have applied and maintaining them moves from messy to overwhelming.

Fortunately, Mercurial includes a powerful extension, Mercurial Queues (or simply “MQ”), that massively simplifies the patch management problem.

The prehistory of Mercurial Queues

During the late 1990s, several Linux kernel developers started to maintain “patch series” that modified the behavior of the Linux kernel. Some of these series were focused on stability, some on feature coverage, and others were more speculative.

The sizes of these patch series grew rapidly. In 2002, Andrew Morton published some shell scripts he had been using to automate the task of managing his patch queues. Andrew was successfully using these scripts to manage hundreds (sometimes thousands) of patches on top of the Linux kernel.

A patchwork quilt

In early 2003, Andreas Gruenbacher and Martin Quinson borrowed the approach of Andrew's scripts and published a tool called “patchwork quilt” [web:quilt], or simply “quilt” (see [gruenbacher:2005] for a paper describing it). Because quilt substantially automated patch management, it rapidly gained a large following among open source software developers.

Quilt manages a stack of patches on top of a directory tree. To begin, you tell quilt to manage a directory tree, and tell it which files you want to manage; it stores away the names and contents of those files. To fix a bug, you create a new patch (using a single command), edit the files you need to fix, then “refresh” the patch.

The refresh step causes quilt to scan the directory tree; it updates the patch with all of the changes you have made. You can create another patch on top of the first, which will track the changes required to modify the tree from “tree with one patch applied” to “tree with two patches applied”.

You can change which patches are applied to the tree. If you “pop” a patch, the changes made by that patch will vanish from the directory tree. Quilt remembers which patches you have popped, though, so you can “push” a popped patch again, and the directory tree will be restored to contain the modifications in the patch. Most importantly, you can run the “refresh” command at any time, and the topmost applied patch will be updated. This means that you can, at any time, change both which patches are applied and what modifications those patches make.

Quilt knows nothing about revision control tools, so it works equally well on top of an unpacked tarball or a Subversion working copy.

From patchwork quilt to Mercurial Queues

In mid-2005, Chris Mason took the features of quilt and wrote an extension that he called Mercurial Queues, which added quilt-like behavior to Mercurial.

The key difference between quilt and MQ is that quilt knows nothing about revision control systems, while MQ is integrated into Mercurial. Each patch that you push is represented as a Mercurial changeset. Pop a patch, and the changeset goes away.

Because quilt does not care about revision control tools, it is still a tremendously useful piece of software to know about for situations where you cannot use Mercurial and MQ.

The huge advantage of MQ

I cannot overstate the value that MQ offers through the unification of patches and revision control.

A major reason that patches have persisted in the free software and open source world—in spite of the availability of increasingly capable revision control tools over the years—is the agility they offer.

Traditional revision control tools make a permanent, irreversible record of everything that you do. While this has great value, it's also somewhat stifling. If you want to perform a wild-eyed experiment, you have to be careful in how you go about it, or you risk leaving unneeded—or worse, misleading or destabilising—traces of your missteps and errors in the permanent revision record.

By contrast, MQ's marriage of distributed revision control with patches makes it much easier to isolate your work. Your patches live on top of normal revision history, and you can make them disappear or reappear at will. If you don't like a patch, you can drop it. If a patch isn't quite as you want it to be, simply fix it—as many times as you need to, until you have refined it into the form you desire.

As an example, the integration of patches with revision control makes understanding patches and debugging their effects—and their interplay with the code they're based on—enormously easier. Since every applied patch has an associated changeset, you can give hg log a file name to see which changesets and patches affected the file. You can use the hg bisect command to binary-search through all changesets and applied patches to see where a bug got introduced or fixed. You can use the hg annotate command to see which changeset or patch modified a particular line of a source file. And so on.

Understanding patches

Because MQ doesn't hide its patch-oriented nature, it is helpful to understand what patches are, and a little about the tools that work with them.

The traditional Unix diff command compares two files, and prints a list of differences between them. The patch command understands these differences as modifications to make to a file. Take a look below for a simple example of these commands in action.

$echo 'this is my original thought' > oldfile$echo 'i have changed my mind' > newfile$diff -u oldfile newfile > tiny.patch$cat tiny.patch--- oldfile 2009-05-05 06:55:37.000000000 +0000 +++ newfile 2009-05-05 06:55:37.000000000 +0000 @@ -1 +1 @@ -this is my original thought +i have changed my mind$patch < tiny.patchpatching file oldfile$cat oldfilei have changed my mind

The type of file that diff generates (and patch takes as input) is called a “patch” or a “diff”; there is no difference between a patch and a diff. (We'll use the term “patch”, since it's more commonly used.)

A patch file can start with arbitrary text; the

patch command ignores this text, but MQ uses

it as the commit message when creating changesets. To find the

beginning of the patch content, patch

searches for the first line that starts with the string

“diff -”.

MQ works with unified diffs (patch can accept several other diff formats, but MQ doesn't). A unified diff contains two kinds of header. The file header describes the file being modified; it contains the name of the file to modify. When patch sees a new file header, it looks for a file with that name to start modifying.

After the file header comes a series of hunks. Each hunk starts with a header; this identifies the range of line numbers within the file that the hunk should modify. Following the header, a hunk starts and ends with a few (usually three) lines of text from the unmodified file; these are called the context for the hunk. If there's only a small amount of context between successive hunks, diff doesn't print a new hunk header; it just runs the hunks together, with a few lines of context between modifications.

Each line of context begins with a space character. Within

the hunk, a line that begins with

“-” means “remove this

line,” while a line that begins with

“+” means “insert this

line.” For example, a line that is modified is

represented by one deletion and one insertion.

We will return to some of the more subtle aspects of patches later (in the section called “More about patches”), but you should have enough information now to use MQ.

Getting started with Mercurial Queues

Because MQ is implemented as an extension, you must

explicitly enable before you can use it. (You don't need to

download anything; MQ ships with the standard Mercurial

distribution.) To enable MQ, edit your ~/.hgrc file, and add the lines

below.

[extensions] hgext.mq =

Once the extension is enabled, it will make a number of new commands available. To verify that the extension is working, you can use hg help to see if the qinit command is now available.

$hg help qinithg qinit [-c] init a new queue repository The queue repository is unversioned by default. If -c is specified, qinit will create a separate nested repository for patches (qinit -c may also be run later to convert an unversioned patch repository into a versioned one). You can use qcommit to commit changes to this queue repository. options: -c --create-repo create queue repository use "hg -v help qinit" to show global options

You can use MQ with any Mercurial repository, and its commands only operate within that repository. To get started, simply prepare the repository using the qinit command.

$hg init mq-sandbox$cd mq-sandbox$echo 'line 1' > file1$echo 'another line 1' > file2$hg add file1 file2$hg commit -m'first change'$hg qinit

This command creates an empty directory called .hg/patches, where

MQ will keep its metadata. As with many Mercurial commands, the

qinit command prints nothing

if it succeeds.

Creating a new patch

To begin work on a new patch, use the qnew command. This command takes one argument, the name of the patch to create.

MQ will use this as the name of an actual file in the

.hg/patches directory, as you

can see below.

$hg tipchangeset: 0:ba8df3126338 tag: tip user: Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> date: Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 summary: first change$hg qnew first.patch$hg tipchangeset: 1:0eef7631d242 tag: qtip tag: first.patch tag: tip tag: qbase user: Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> date: Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 summary: [mq]: first.patch$ls .hg/patchesfirst.patch series status

Also newly present in the .hg/patches directory are two

other files, series and

status. The series file lists all of the

patches that MQ knows about for this repository, with one

patch per line. Mercurial uses the status file for internal

book-keeping; it tracks all of the patches that MQ has

applied in this repository.

Once you have created your new patch, you can edit files in the working directory as you usually would. All of the normal Mercurial commands, such as hg diff and hg annotate, work exactly as they did before.

Refreshing a patch

When you reach a point where you want to save your work, use the qrefresh command to update the patch you are working on.

$echo 'line 2' >> file1$hg diffdiff -r 0eef7631d242 file1 --- a/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 +++ b/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 @@ -1,1 +1,2 @@ line 1 +line 2$hg qrefresh$hg diff$hg tip --style=compact --patch1[qtip,first.patch,tip,qbase] b737e7b1c206 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos [mq]: first.patch diff -r ba8df3126338 -r b737e7b1c206 file1 --- a/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 +++ b/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 @@ -1,1 +1,2 @@ line 1 +line 2

This command folds the changes you have made in the working directory into your patch, and updates its corresponding changeset to contain those changes.

You can run qrefresh as often as you like, so it's a good way to “checkpoint” your work. Refresh your patch at an opportune time; try an experiment; and if the experiment doesn't work out, hg revert your modifications back to the last time you refreshed.

$echo 'line 3' >> file1$hg statusM file1$hg qrefresh$hg tip --style=compact --patch1[qtip,first.patch,tip,qbase] a2efdba241e8 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos [mq]: first.patch diff -r ba8df3126338 -r a2efdba241e8 file1 --- a/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:41 2009 +0000 +++ b/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:42 2009 +0000 @@ -1,1 +1,3 @@ line 1 +line 2 +line 3

Stacking and tracking patches

Once you have finished working on a patch, or need to work on another, you can use the qnew command again to create a new patch. Mercurial will apply this patch on top of your existing patch.

$hg qnew second.patch$hg log --style=compact --limit=22[qtip,second.patch,tip] 4bb84cd8876a 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos [mq]: second.patch 1[first.patch,qbase] a2efdba241e8 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos [mq]: first.patch$echo 'line 4' >> file1$hg qrefresh$hg tip --style=compact --patch2[qtip,second.patch,tip] 8287e9f12f96 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos [mq]: second.patch diff -r a2efdba241e8 -r 8287e9f12f96 file1 --- a/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:42 2009 +0000 +++ b/file1 Tue May 05 06:55:42 2009 +0000 @@ -1,3 +1,4 @@ line 1 line 2 line 3 +line 4$hg annotate file10: line 1 1: line 2 1: line 3 2: line 4

Notice that the patch contains the changes in our prior patch as part of its context (you can see this more clearly in the output of hg annotate).

So far, with the exception of qnew and qrefresh, we've been careful to only use regular Mercurial commands. However, MQ provides many commands that are easier to use when you are thinking about patches, as illustrated below.

$hg qseriesfirst.patch second.patch$hg qappliedfirst.patch second.patch

Manipulating the patch stack

The previous discussion implied that there must be a difference between “known” and “applied” patches, and there is. MQ can manage a patch without it being applied in the repository.

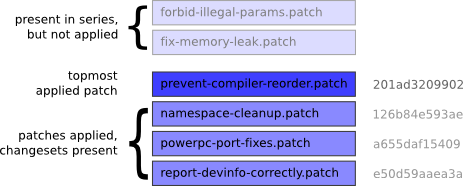

An applied patch has a corresponding changeset in the repository, and the effects of the patch and changeset are visible in the working directory. You can undo the application of a patch using the qpop command. MQ still knows about, or manages, a popped patch, but the patch no longer has a corresponding changeset in the repository, and the working directory does not contain the changes made by the patch. Figure 12.1, “Applied and unapplied patches in the MQ patch stack” illustrates the difference between applied and tracked patches.

You can reapply an unapplied, or popped, patch using the qpush command. This creates a new changeset to correspond to the patch, and the patch's changes once again become present in the working directory. See below for examples of qpop and qpush in action.

$hg qappliedfirst.patch second.patch$hg qpopnow at: first.patch$hg qseriesfirst.patch second.patch$hg qappliedfirst.patch$cat file1line 1 line 2 line 3

Notice that once we have popped a patch or two patches, the output of qseries remains the same, while that of qapplied has changed.

Pushing and popping many patches

While qpush and

qpop each operate on a

single patch at a time by default, you can push and pop many

patches in one go. The hg -a option to

qpush causes it to push

all unapplied patches, while the -a option to qpop causes it to pop all applied

patches. (For some more ways to push and pop many patches,

see the section called “Getting the best performance out of MQ” below.)

$hg qpush -aapplying second.patch now at: second.patch$cat file1line 1 line 2 line 3 line 4

Safety checks, and overriding them

Several MQ commands check the working directory before

they do anything, and fail if they find any modifications.

They do this to ensure that you won't lose any changes that

you have made, but not yet incorporated into a patch. The

example below illustrates this; the qnew command will not create a

new patch if there are outstanding changes, caused in this

case by the hg add of

file3.

$echo 'file 3, line 1' >> file3$hg qnew add-file3.patch$hg qnew -f add-file3.patchabort: patch "add-file3.patch" already exists

Commands that check the working directory all take an

“I know what I'm doing” option, which is always

named -f. The exact meaning of

-f depends on the command. For example,

hg qnew hg -f

will incorporate any outstanding changes into the new patch it

creates, but hg qpop hg -f

will revert modifications to any files affected by the patch

that it is popping. Be sure to read the documentation for a

command's -f option before you use it!

Working on several patches at once

The qrefresh command always refreshes the topmost applied patch. This means that you can suspend work on one patch (by refreshing it), pop or push to make a different patch the top, and work on that patch for a while.

Here's an example that illustrates how you can use this ability. Let's say you're developing a new feature as two patches. The first is a change to the core of your software, and the second—layered on top of the first—changes the user interface to use the code you just added to the core. If you notice a bug in the core while you're working on the UI patch, it's easy to fix the core. Simply qrefresh the UI patch to save your in-progress changes, and qpop down to the core patch. Fix the core bug, qrefresh the core patch, and qpush back to the UI patch to continue where you left off.

More about patches

MQ uses the GNU patch command to apply patches, so it's helpful to know a few more detailed aspects of how patch works, and about patches themselves.

The strip count

If you look at the file headers in a patch, you will notice that the pathnames usually have an extra component on the front that isn't present in the actual path name. This is a holdover from the way that people used to generate patches (people still do this, but it's somewhat rare with modern revision control tools).

Alice would unpack a tarball, edit her files, then decide

that she wanted to create a patch. So she'd rename her

working directory, unpack the tarball again (hence the need

for the rename), and use the -r and -N options to

diff to recursively generate a patch

between the unmodified directory and the modified one. The

result would be that the name of the unmodified directory

would be at the front of the left-hand path in every file

header, and the name of the modified directory would be at the

front of the right-hand path.

Since someone receiving a patch from the Alices of the net

would be unlikely to have unmodified and modified directories

with exactly the same names, the patch

command has a -p option

that indicates the number of leading path name components to

strip when trying to apply a patch. This number is called the

strip count.

An option of “-p1” means

“use a strip count of one”. If

patch sees a file name

foo/bar/baz in a file header, it will

strip foo and try to patch a file named

bar/baz. (Strictly speaking, the strip

count refers to the number of path

separators (and the components that go with them

) to strip. A strip count of one will turn

foo/bar into bar,

but /foo/bar (notice the extra leading

slash) into foo/bar.)

The “standard” strip count for patches is one; almost all patches contain one leading path name component that needs to be stripped. Mercurial's hg diff command generates path names in this form, and the hg import command and MQ expect patches to have a strip count of one.

If you receive a patch from someone that you want to add

to your patch queue, and the patch needs a strip count other

than one, you cannot just qimport the patch, because

qimport does not yet have

a -p option (see issue

311). Your best bet is to qnew a patch of your own, then

use patch -pN to apply their patch,

followed by hg addremove to

pick up any files added or removed by the patch, followed by

hg qrefresh. This

complexity may become unnecessary; see issue

311 for details.

Strategies for applying a patch

When patch applies a hunk, it tries a handful of successively less accurate strategies to try to make the hunk apply. This falling-back technique often makes it possible to take a patch that was generated against an old version of a file, and apply it against a newer version of that file.

First, patch tries an exact match, where the line numbers, the context, and the text to be modified must apply exactly. If it cannot make an exact match, it tries to find an exact match for the context, without honouring the line numbering information. If this succeeds, it prints a line of output saying that the hunk was applied, but at some offset from the original line number.

If a context-only match fails, patch removes the first and last lines of the context, and tries a reduced context-only match. If the hunk with reduced context succeeds, it prints a message saying that it applied the hunk with a fuzz factor (the number after the fuzz factor indicates how many lines of context patch had to trim before the patch applied).

When neither of these techniques works,

patch prints a message saying that the hunk

in question was rejected. It saves rejected hunks (also

simply called “rejects”) to a file with the same

name, and an added .rej

extension. It also saves an unmodified copy of the file with

a .orig extension; the

copy of the file without any extensions will contain any

changes made by hunks that did apply

cleanly. If you have a patch that modifies

foo with six hunks, and one of them fails

to apply, you will have: an unmodified

foo.orig, a foo.rej

containing one hunk, and foo, containing

the changes made by the five successful hunks.

Some quirks of patch representation

There are a few useful things to know about how patch works with files.

This should already be obvious, but patch cannot handle binary files.

Neither does it care about the executable bit; it creates new files as readable, but not executable.

patch treats the removal of a file as a diff between the file to be removed and the empty file. So your idea of “I deleted this file” looks like “every line of this file was deleted” in a patch.

It treats the addition of a file as a diff between the empty file and the file to be added. So in a patch, your idea of “I added this file” looks like “every line of this file was added”.

It treats a renamed file as the removal of the old name, and the addition of the new name. This means that renamed files have a big footprint in patches. (Note also that Mercurial does not currently try to infer when files have been renamed or copied in a patch.)

patch cannot represent empty files, so you cannot use a patch to represent the notion “I added this empty file to the tree”.

Beware the fuzz

While applying a hunk at an offset, or with a fuzz factor, will often be completely successful, these inexact techniques naturally leave open the possibility of corrupting the patched file. The most common cases typically involve applying a patch twice, or at an incorrect location in the file. If patch or qpush ever mentions an offset or fuzz factor, you should make sure that the modified files are correct afterwards.

It's often a good idea to refresh a patch that has applied with an offset or fuzz factor; refreshing the patch generates new context information that will make it apply cleanly. I say “often,” not “always,” because sometimes refreshing a patch will make it fail to apply against a different revision of the underlying files. In some cases, such as when you're maintaining a patch that must sit on top of multiple versions of a source tree, it's acceptable to have a patch apply with some fuzz, provided you've verified the results of the patching process in such cases.

Handling rejection

If qpush fails to

apply a patch, it will print an error message and exit. If it

has left .rej files

behind, it is usually best to fix up the rejected hunks before

you push more patches or do any further work.

If your patch used to apply cleanly, and no longer does because you've changed the underlying code that your patches are based on, Mercurial Queues can help; see the section called “Updating your patches when the underlying code changes” for details.

Unfortunately, there aren't any great techniques for

dealing with rejected hunks. Most often, you'll need to view

the .rej file and edit the

target file, applying the rejected hunks by hand.

A Linux kernel hacker, Chris Mason (the author of Mercurial Queues), wrote a tool called mpatch (http://oss.oracle.com/~mason/mpatch/), which takes a simple approach to automating the application of hunks rejected by patch. The mpatch command can help with four common reasons that a hunk may be rejected:

If you use mpatch, you should be doubly careful to check your results when you're done. In fact, mpatch enforces this method of double-checking the tool's output, by automatically dropping you into a merge program when it has done its job, so that you can verify its work and finish off any remaining merges.

More on patch management

As you grow familiar with MQ, you will find yourself wanting to perform other kinds of patch management operations.

Deleting unwanted patches

If you want to get rid of a patch, use the hg qdelete command to delete the patch file and remove its entry from the patch series. If you try to delete a patch that is still applied, hg qdelete will refuse.

$hg init myrepo$cd myrepo$hg qinit$hg qnew bad.patch$echo a > a$hg add a$hg qrefresh$hg qdelete bad.patchabort: cannot delete applied patch bad.patch$hg qpoppatch queue now empty$hg qdelete bad.patch

Converting to and from permanent revisions

Once you're done working on a patch and want to turn it into a permanent changeset, use the hg qfinish command. Pass a revision to the command to identify the patch that you want to turn into a regular changeset; this patch must already be applied.

$hg qnew good.patch$echo a > a$hg add a$hg qrefresh -m 'Good change'$hg qfinish tip$hg qapplied$hg tip --style=compact0[tip] 1a7ef9f28379 2009-05-05 06:55 +0000 bos Good change

The hg qfinish command

accepts an --all or -a

option, which turns all applied patches into regular

changesets.

It is also possible to turn an existing changeset into a

patch, by passing the -r option to hg qimport.

$hg qimport -r tip$hg qapplied0.diff

Note that it only makes sense to convert a changeset into a patch if you have not propagated that changeset into any other repositories. The imported changeset's ID will change every time you refresh the patch, which will make Mercurial treat it as unrelated to the original changeset if you have pushed it somewhere else.

Getting the best performance out of MQ

MQ is very efficient at handling a large number of patches. I ran some performance experiments in mid-2006 for a talk that I gave at the 2006 EuroPython conference (on modern hardware, you should expect better performance than you'll see below). I used as my data set the Linux 2.6.17-mm1 patch series, which consists of 1,738 patches. I applied these on top of a Linux kernel repository containing all 27,472 revisions between Linux 2.6.12-rc2 and Linux 2.6.17.

On my old, slow laptop, I was able to hg qpush hg -a all

1,738 patches in 3.5 minutes, and hg qpop

hg -a

them all in 30 seconds. (On a newer laptop, the time to push

all patches dropped to two minutes.) I could qrefresh one of the biggest patches

(which made 22,779 lines of changes to 287 files) in 6.6

seconds.

Clearly, MQ is well suited to working in large trees, but there are a few tricks you can use to get the best performance of it.

First of all, try to “batch” operations together. Every time you run qpush or qpop, these commands scan the working directory once to make sure you haven't made some changes and then forgotten to run qrefresh. On a small tree, the time that this scan takes is unnoticeable. However, on a medium-sized tree (containing tens of thousands of files), it can take a second or more.

The qpush and qpop commands allow you to push and pop multiple patches at a time. You can identify the “destination patch” that you want to end up at. When you qpush with a destination specified, it will push patches until that patch is at the top of the applied stack. When you qpop to a destination, MQ will pop patches until the destination patch is at the top.

You can identify a destination patch using either the name of the patch, or by number. If you use numeric addressing, patches are counted from zero; this means that the first patch is zero, the second is one, and so on.

Updating your patches when the underlying code changes

It's common to have a stack of patches on top of an underlying repository that you don't modify directly. If you're working on changes to third-party code, or on a feature that is taking longer to develop than the rate of change of the code beneath, you will often need to sync up with the underlying code, and fix up any hunks in your patches that no longer apply. This is called rebasing your patch series.

The simplest way to do this is to hg

qpop hg

-a your patches, then hg pull changes into the underlying

repository, and finally hg qpush hg -a your

patches again. MQ will stop pushing any time it runs across a

patch that fails to apply during conflicts, allowing you to fix

your conflicts, qrefresh the

affected patch, and continue pushing until you have fixed your

entire stack.

This approach is easy to use and works well if you don't expect changes to the underlying code to affect how well your patches apply. If your patch stack touches code that is modified frequently or invasively in the underlying repository, however, fixing up rejected hunks by hand quickly becomes tiresome.

It's possible to partially automate the rebasing process. If your patches apply cleanly against some revision of the underlying repo, MQ can use this information to help you to resolve conflicts between your patches and a different revision.

The process is a little involved.

To begin, hg qpush -a all of your patches on top of the revision where you know that they apply cleanly.

Save a backup copy of your patch directory using hg qsave

hg -ehg -c. This prints the name of the directory that it has saved the patches in. It will save the patches to a directory called.hg/patches.N, whereNis a small integer. It also commits a “save changeset” on top of your applied patches; this is for internal book-keeping, and records the states of theseriesandstatusfiles.Use hg pull to bring new changes into the underlying repository. (Don't run hg pull -u; see below for why.)

Update to the new tip revision, using hg update

-Cto override the patches you have pushed.Merge all patches using hg qpush -m -a. The

-moption to qpush tells MQ to perform a three-way merge if the patch fails to apply.

During the hg qpush hg -m,

each patch in the series

file is applied normally. If a patch applies with fuzz or

rejects, MQ looks at the queue you qsaved, and performs a three-way

merge with the corresponding changeset. This merge uses

Mercurial's normal merge machinery, so it may pop up a GUI merge

tool to help you to resolve problems.

When you finish resolving the effects of a patch, MQ refreshes your patch based on the result of the merge.

At the end of this process, your repository will have one

extra head from the old patch queue, and a copy of the old patch

queue will be in .hg/patches.N. You can remove the

extra head using hg qpop -a -n

patches.N or hg

strip. You can delete .hg/patches.N once you are sure

that you no longer need it as a backup.

Identifying patches

MQ commands that work with patches let you refer to a patch

either by using its name or by a number. By name is obvious

enough; pass the name foo.patch to qpush, for example, and it will

push patches until foo.patch is

applied.

As a shortcut, you can refer to a patch using both a name

and a numeric offset; foo.patch-2 means

“two patches before foo.patch”,

while bar.patch+4 means “four patches

after bar.patch”.

Referring to a patch by index isn't much different. The first patch printed in the output of qseries is patch zero (yes, it's one of those start-at-zero counting systems); the second is patch one; and so on.

MQ also makes it easy to work with patches when you are

using normal Mercurial commands. Every command that accepts a

changeset ID will also accept the name of an applied patch. MQ

augments the tags normally in the repository with an eponymous

one for each applied patch. In addition, the special tags

qbase and

qtip identify

the “bottom-most” and topmost applied patches,

respectively.

These additions to Mercurial's normal tagging capabilities make dealing with patches even more of a breeze.

Want to patchbomb a mailing list with your latest series of changes?

hg email qbase:qtip

(Don't know what “patchbombing” is? See the section called “Send changes via email with the patchbomb extension”.)

Need to see all of the patches since

foo.patchthat have touched files in a subdirectory of your tree?hg log -r foo.patch:qtip subdir

Because MQ makes the names of patches available to the rest of Mercurial through its normal internal tag machinery, you don't need to type in the entire name of a patch when you want to identify it by name.

Another nice consequence of representing patch names as tags is that when you run the hg log command, it will display a patch's name as a tag, simply as part of its normal output. This makes it easy to visually distinguish applied patches from underlying “normal” revisions. The following example shows a few normal Mercurial commands in use with applied patches.

$hg qappliedfirst.patch second.patch$hg log -r qbase:qtipchangeset: 1:229b588a973c tag: first.patch tag: qbase user: Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> date: Tue May 05 06:55:39 2009 +0000 summary: [mq]: first.patch changeset: 2:08539aceda54 tag: qtip tag: second.patch tag: tip user: Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> date: Tue May 05 06:55:39 2009 +0000 summary: [mq]: second.patch$hg export second.patch# HG changeset patch # User Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> # Date 1241506539 0 # Node ID 08539aceda548e75d84aac5f55171a2d2861da60 # Parent 229b588a973c6e1f5d66e48a5228ff61c4cb3995 [mq]: second.patch diff -r 229b588a973c -r 08539aceda54 other.c --- /dev/null Thu Jan 01 00:00:00 1970 +0000 +++ b/other.c Tue May 05 06:55:39 2009 +0000 @@ -0,0 +1,1 @@ +double u;

Useful things to know about

There are a number of aspects of MQ usage that don't fit tidily into sections of their own, but that are good to know. Here they are, in one place.

Normally, when you qpop a patch and qpush it again, the changeset that represents the patch after the pop/push will have a different identity than the changeset that represented the hash beforehand. See the section called “qpush—push patches onto the stack” for information as to why this is.

It's not a good idea to hg merge changes from another branch with a patch changeset, at least if you want to maintain the “patchiness” of that changeset and changesets below it on the patch stack. If you try to do this, it will appear to succeed, but MQ will become confused.

Managing patches in a repository

Because MQ's .hg/patches directory resides

outside a Mercurial repository's working directory, the

“underlying” Mercurial repository knows nothing

about the management or presence of patches.

This presents the interesting possibility of managing the contents of the patch directory as a Mercurial repository in its own right. This can be a useful way to work. For example, you can work on a patch for a while, qrefresh it, then hg commit the current state of the patch. This lets you “roll back” to that version of the patch later on.

You can then share different versions of the same patch stack among multiple underlying repositories. I use this when I am developing a Linux kernel feature. I have a pristine copy of my kernel sources for each of several CPU architectures, and a cloned repository under each that contains the patches I am working on. When I want to test a change on a different architecture, I push my current patches to the patch repository associated with that kernel tree, pop and push all of my patches, and build and test that kernel.

Managing patches in a repository makes it possible for multiple developers to work on the same patch series without colliding with each other, all on top of an underlying source base that they may or may not control.

MQ support for patch repositories

MQ helps you to work with the .hg/patches directory as a

repository; when you prepare a repository for working with

patches using qinit, you

can pass the hg

-c option to create the .hg/patches directory as a

Mercurial repository.

As a convenience, if MQ notices that the .hg/patches directory is a

repository, it will automatically hg

add every patch that you create and import.

MQ provides a shortcut command, qcommit, that runs hg commit in the .hg/patches

directory. This saves some bothersome typing.

Finally, as a convenience to manage the patch directory,

you can define the alias mq on Unix

systems. For example, on Linux systems using the

bash shell, you can include the following

snippet in your ~/.bashrc.

alias mq=`hg -R $(hg root)/.hg/patches'

You can then issue commands of the form mq pull from the main repository.

A few things to watch out for

MQ's support for working with a repository full of patches is limited in a few small respects.

MQ cannot automatically detect changes that you make to

the patch directory. If you hg

pull, manually edit, or hg

update changes to patches or the series file, you will have to

hg qpop hg -a and

then hg qpush hg -a in

the underlying repository to see those changes show up there.

If you forget to do this, you can confuse MQ's idea of which

patches are applied.

Third party tools for working with patches

Once you've been working with patches for a while, you'll find yourself hungry for tools that will help you to understand and manipulate the patches you're dealing with.

The diffstat command

[web:diffstat] generates a histogram of the

modifications made to each file in a patch. It provides a good

way to “get a sense of” a patch—which files

it affects, and how much change it introduces to each file and

as a whole. (I find that it's a good idea to use

diffstat's -p option as a matter of

course, as otherwise it will try to do clever things with

prefixes of file names that inevitably confuse at least

me.)

$diffstat -p1 remove-redundant-null-checks.patchdrivers/char/agp/sgi-agp.c | 5 ++--- drivers/char/hvcs.c | 11 +++++------ drivers/message/fusion/mptfc.c | 6 ++---- drivers/message/fusion/mptsas.c | 3 +-- drivers/net/fs_enet/fs_enet-mii.c | 3 +-- drivers/net/wireless/ipw2200.c | 22 ++++++---------------- drivers/scsi/libata-scsi.c | 4 +--- drivers/video/au1100fb.c | 3 +-- 8 files changed, 19 insertions(+), 38 deletions(-)$filterdiff -i '*/video/*' remove-redundant-null-checks.patch--- a/drivers/video/au1100fb.c~remove-redundant-null-checks-before-free-in-drivers +++ a/drivers/video/au1100fb.c @@ -743,8 +743,7 @@ void __exit au1100fb_cleanup(void) { driver_unregister(&au1100fb_driver); - if (drv_info.opt_mode) - kfree(drv_info.opt_mode); + kfree(drv_info.opt_mode); } module_init(au1100fb_init);

The patchutils package

[web:patchutils] is invaluable. It provides a

set of small utilities that follow the “Unix

philosophy;” each does one useful thing with a patch.

The patchutils command I use

most is filterdiff, which extracts subsets

from a patch file. For example, given a patch that modifies

hundreds of files across dozens of directories, a single

invocation of filterdiff can generate a

smaller patch that only touches files whose names match a

particular glob pattern. See the section called “Viewing the history of a patch” for another

example.

Good ways to work with patches

Whether you are working on a patch series to submit to a free software or open source project, or a series that you intend to treat as a sequence of regular changesets when you're done, you can use some simple techniques to keep your work well organized.

Give your patches descriptive names. A good name for a

patch might be rework-device-alloc.patch,

because it will immediately give you a hint what the purpose of

the patch is. Long names shouldn't be a problem; you won't be

typing the names often, but you will be

running commands like qapplied and qtop over and over. Good naming

becomes especially important when you have a number of patches

to work with, or if you are juggling a number of different tasks

and your patches only get a fraction of your attention.

Be aware of what patch you're working on. Use the qtop command and skim over the text

of your patches frequently—for example, using hg tip -p)—to be sure

of where you stand. I have several times worked on and qrefreshed a patch other than the

one I intended, and it's often tricky to migrate changes into

the right patch after making them in the wrong one.

For this reason, it is very much worth investing a little time to learn how to use some of the third-party tools I described in the section called “Third party tools for working with patches”, particularly diffstat and filterdiff. The former will give you a quick idea of what changes your patch is making, while the latter makes it easy to splice hunks selectively out of one patch and into another.

MQ cookbook

Manage “trivial” patches

Because the overhead of dropping files into a new Mercurial repository is so low, it makes a lot of sense to manage patches this way even if you simply want to make a few changes to a source tarball that you downloaded.

Begin by downloading and unpacking the source tarball, and turning it into a Mercurial repository.

$download netplug-1.2.5.tar.bz2$tar jxf netplug-1.2.5.tar.bz2$cd netplug-1.2.5$hg init$hg commit -q --addremove --message netplug-1.2.5$cd ..$hg clone netplug-1.2.5 netplugupdating working directory 18 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved

Continue by creating a patch stack and making your changes.

$cd netplug$hg qinit$hg qnew -m 'fix build problem with gcc 4' build-fix.patch$perl -pi -e 's/int addr_len/socklen_t addr_len/' netlink.c$hg qrefresh$hg tip -pchangeset: 1:355c94c5387f tag: qtip tag: build-fix.patch tag: tip tag: qbase user: Bryan O'Sullivan <[email protected]> date: Tue May 05 06:55:40 2009 +0000 summary: fix build problem with gcc 4 diff -r cec109bd7cd3 -r 355c94c5387f netlink.c --- a/netlink.c Tue May 05 06:55:39 2009 +0000 +++ b/netlink.c Tue May 05 06:55:40 2009 +0000 @@ -275,7 +275,7 @@ exit(1); } - int addr_len = sizeof(addr); + socklen_t addr_len = sizeof(addr); if (getsockname(fd, (struct sockaddr *) &addr, &addr_len) == -1) { do_log(LOG_ERR, "Could not get socket details: %m");

Let's say a few weeks or months pass, and your package author releases a new version. First, bring their changes into the repository.

$hg qpop -apatch queue now empty$cd ..$download netplug-1.2.8.tar.bz2$hg clone netplug-1.2.5 netplug-1.2.8updating working directory 18 files updated, 0 files merged, 0 files removed, 0 files unresolved$cd netplug-1.2.8$hg locate -0 | xargs -0 rm$cd ..$tar jxf netplug-1.2.8.tar.bz2$cd netplug-1.2.8$hg commit --addremove --message netplug-1.2.8

The pipeline starting with hg

locate above deletes all files in the working

directory, so that hg

commit's --addremove option can

actually tell which files have really been removed in the

newer version of the source.

Finally, you can apply your patches on top of the new tree.

$cd ../netplug$hg pull ../netplug-1.2.8pulling from ../netplug-1.2.8 searching for changes adding changesets adding manifests adding file changes added 1 changesets with 12 changes to 12 files (run 'hg update' to get a working copy)$hg qpush -a(working directory not at tip) applying build-fix.patch now at: build-fix.patch

Combining entire patches

MQ provides a command, qfold that lets you combine entire patches. This “folds” the patches you name, in the order you name them, into the topmost applied patch, and concatenates their descriptions onto the end of its description. The patches that you fold must be unapplied before you fold them.

The order in which you fold patches matters. If your

topmost applied patch is foo, and you

qfold

bar and quux into it,

you will end up with a patch that has the same effect as if

you applied first foo, then

bar, followed by

quux.

Merging part of one patch into another

Merging part of one patch into another is more difficult than combining entire patches.

If you want to move changes to entire files, you can use

filterdiff's -i and -x options to choose the

modifications to snip out of one patch, concatenating its

output onto the end of the patch you want to merge into. You

usually won't need to modify the patch you've merged the

changes from. Instead, MQ will report some rejected hunks

when you qpush it (from

the hunks you moved into the other patch), and you can simply

qrefresh the patch to drop

the duplicate hunks.

If you have a patch that has multiple hunks modifying a file, and you only want to move a few of those hunks, the job becomes more messy, but you can still partly automate it. Use lsdiff -nvv to print some metadata about the patch.

$lsdiff -nvv remove-redundant-null-checks.patch22 File #1 a/drivers/char/agp/sgi-agp.c 24 Hunk #1 static int __devinit agp_sgi_init(void) 37 File #2 a/drivers/char/hvcs.c 39 Hunk #1 static struct tty_operations hvcs_ops = 53 Hunk #2 static int hvcs_alloc_index_list(int n) 69 File #3 a/drivers/message/fusion/mptfc.c 71 Hunk #1 mptfc_GetFcDevPage0(MPT_ADAPTER *ioc, in 85 File #4 a/drivers/message/fusion/mptsas.c 87 Hunk #1 mptsas_probe_hba_phys(MPT_ADAPTER *ioc) 98 File #5 a/drivers/net/fs_enet/fs_enet-mii.c 100 Hunk #1 static struct fs_enet_mii_bus *create_bu 111 File #6 a/drivers/net/wireless/ipw2200.c 113 Hunk #1 static struct ipw_fw_error *ipw_alloc_er 126 Hunk #2 static ssize_t clear_error(struct device 140 Hunk #3 static void ipw_irq_tasklet(struct ipw_p 150 Hunk #4 static void ipw_pci_remove(struct pci_de 164 File #7 a/drivers/scsi/libata-scsi.c 166 Hunk #1 int ata_cmd_ioctl(struct scsi_device *sc 178 File #8 a/drivers/video/au1100fb.c 180 Hunk #1 void __exit au1100fb_cleanup(void)

This command prints three different kinds of number:

You'll have to use some visual inspection, and reading of

the patch, to identify the file and hunk numbers you'll want,

but you can then pass them to to

filterdiff's --files and --hunks options, to

select exactly the file and hunk you want to extract.

Once you have this hunk, you can concatenate it onto the end of your destination patch and continue with the remainder of the section called “Combining entire patches”.

Differences between quilt and MQ

If you are already familiar with quilt, MQ provides a similar command set. There are a few differences in the way that it works.

You will already have noticed that most quilt commands have

MQ counterparts that simply begin with a

“q”. The exceptions are quilt's

add and remove commands,

the counterparts for which are the normal Mercurial hg add and hg

remove commands. There is no MQ equivalent of the

quilt edit command.

![[Note]](figs/note.png)

Want to stay up to date? Subscribe to the comment feed for

Want to stay up to date? Subscribe to the comment feed for